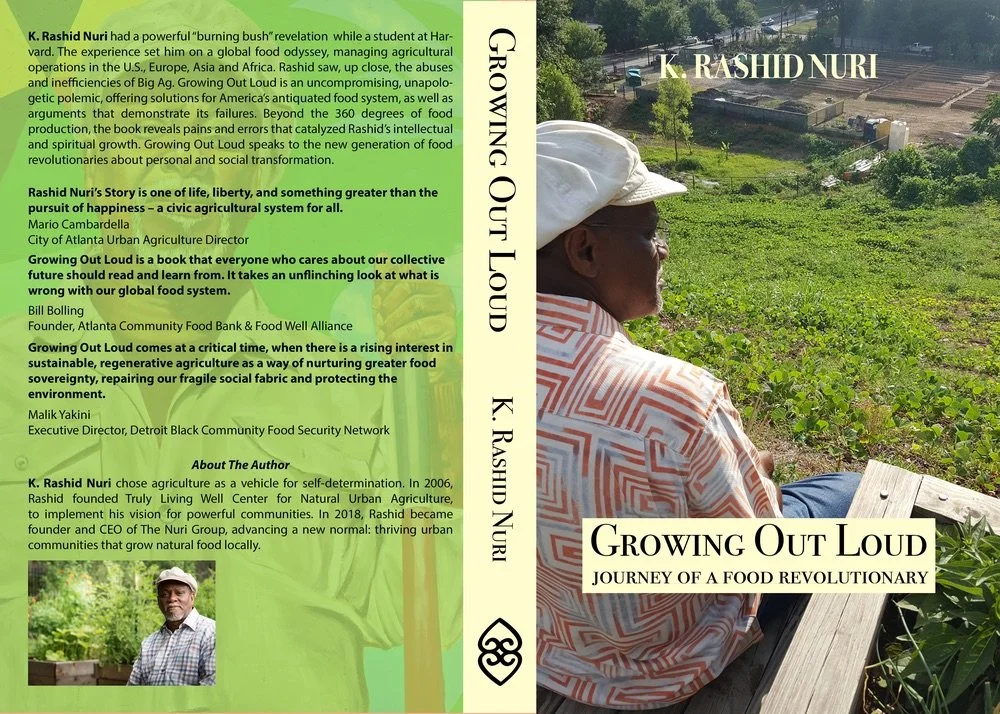

Growing Out Loud: Journey of a Food Revolutionary

BY K. RASHID NURI

ABOUT THE AUTOR

Connecting Urban Dwellers with the Land

In this excerpt from Growing Out Loud: Journey of a Food Revolutionary, K. Rashid Nuri speaks frankly about the rigors of building Truly Living Well Center for Urban Agriculture in Atlanta (TLW). He was sustained by a vision of connecting people with the land, providing healthy food and reversing the trend of Black land loss and food insecurity. Rashid says that he was highly motivated to “build the world that he wanted for his children and grandchildren.

During his tenure at the helm of TLW, the organization was a pioneer in Atlanta’s good food movement, leading the way as hundreds of urban farms and community gardens sprang up around the metro area. Truly Living Well was the culmination of Rashid’s 35-year global tour of the agricultural industry, from the beautiful vineyards of California’s Napa Valley, to the farms of the Nation of Islam in the Deep South, to commodity production and distribution overseen by ag giant Cargill in Asia and Africa. Other stops along the way included the USDA during the Clinton Administration.

During his years at USDA, Rashid saw—up close—the abuses and inefficiencies of Big Ag. After his experience at the USDA, Rashid's vision of community food sovereignty and food equity emerged with total clarity. He came full circle from starting the first organic gardens in San Diego, to founding Atlanta's premier urban agricultural organization, which grew tons of chemical-free, nutritious food, providing jobs and educating communities about food, nutrition and self-sufficiency.

Growing Out Loud chronicles Rashid’s journeys and the failing state of the food supply, offering timely and valuable guidance for the new food movement.

Excerpt from

Growing Out Loud: Journey of a Food Revolutionary

© 2018

“Individual commitment to a group effort—that is what makes a team work,

a company work, a society work, a civilization work.”

Vince Lombardi

Chapter 22

Truly Living Well 2.0

My eldest son moved to Georgia in 2009. Kamal left a banking career in New York and chose to work unpaid with Truly Living Well for the next two and a half years. It was during his tenure that TLW evolved to the next level. We realized that the organization was actually an educational institute, predicated upon urban agricultural production as its base. We were teaching people how to grow food; we were reconnecting people back to the land. We were helping people understand more about their food, reacquainting them with their food in ways previously unimagined. Our real work was building community, with food production as the foundation of our work.

The work needed continuing financial support. Sevananda provided the very first grant that we received, $5000. Sevananda is the largest customer-owned food cooperative in Metro Atlanta. The Environmental Protection Agency gave us $10,000, and later, $75,000. I was so happy and proud that I unwittingly made a grave error, by announcing the amount of the awards in our newsletter. I immediately started getting phone calls and emails asking for jobs, gifts and contracts. For an individual, a gift of $75,000 is a lot of money. However, for a fledgling organization like TLW, the money was a drop in the bucket in relation to the work we had to do. From that point until his departure, Kamal assumed responsibility for financial development and successfully wrote a number of grants on behalf of TLW that proved critical to our growth.

I took advantage of every opportunity to speak at meetings and before groups. I taught at public libraries and to children at schools. We conducted classes and educational tours, primarily at our East Point location. A six-weekend series was the most thorough training we conducted, until we formed a partnership with Historic Westside Gardens and Fulton Atlanta Community Action Authority to implement a training grant. That collaboration enabled us to conduct a hands-on training program, five days a week for 10 consecutive weeks. Trainees were recruited from the Vine City/English Avenue neighborhoods. The first cohort was comprised of 10 students.

The success of the collaboration and the burgeoning interest in urban agriculture, agricultural education and farm-to-school programs led us to revise and upgrade our business plans. Americans were expressing concerns about the health risks of pesticides, hormones, antibiotics and other chemicals used in food production. Consumers also felt that small-scale family farms were more likely to care about food safety than large-scale industrial farms. It became important to people to know whether their food was grown or produced locally or regionally.

Trends in the tourist industry showed an increasing demand for experiential, hands-on tourism activities. As the U.S. population grows and continues to rapidly urbanize, consumers who travel increasingly favor experiences over traditional goods and services. They want more than just a trip or a hotel stay—they want a living, breathing experience. We wanted to provide people with that experience.

Agritourism was one of the fastest growing segments. This segment focuses on travel that is low-impact and empowering to local communities, socially and economically. Parents wanted their children to know how food is grown and that milk actually comes from a cow—not a carton—and that peanuts do not grow on trees.

At this point, it became clear that TLW needed a larger venue to implement our plans. I used a shotgun approach, looking at every possibility shown to us, in attempting to find a new home for our work. After an exhaustive search, in 2009 Truly Living Well explored developing a farm on the site of the former Wheat Street Gardens Apartments.

For 52 years, the Reverend William Holmes Borders served as Pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church in Atlanta. He campaigned for civil rights and distinguished himself as a leader and spokesman for the city's poor, Black and dispossessed. Borders was instrumental in the hiring of Atlanta's first Black police officers in the 1940s. He led the campaign to desegregate the city's public transportation in the 1950s and established the nation's first federally subsidized, church-operated rental housing project in the 1960s.

By the time we came along, Wheat Street Gardens apartment complex had come into significant disrepair. All the former tenants were dispersed far and wide. The Wheat Street Charitable Foundation technically owned the housing complex. Its demolition left an 11-acre open area in the middle of the Old Fourth Ward, near downtown Atlanta. As soon as I saw the site, I was determined to make it our premier location and demonstration farm, right in the shadows of the downtown skyscrapers.

Charles Whatley, of the Atlanta Development Authority, brought us to the table with the Wheat Street Charitable Foundation. He was waiting on Congressional re-approval of Empowerment Zone funding to finance the project. Whatley introduced us to a group that grew potted plants on several large farms in Florida that was also interested in the site. We visited their operation and had lengthy discussions about possible collaboration. There were multiple problems with the potential deal. Foremost was that their operation was not organic. Second, and most important, the dollars in their proposal did not make sense. They essentially wanted TLW to provide labor for their endeavor. We turned it down.

During this time, we put together our own coalition, avidly interested in making the project a reality. This group included Atlanta City Councilman Kwanza Hall, GA Tech, the Georgia Department of Health and several large foundations. We realized it was incumbent upon us to raise private funds to launch the project, rather than continue waiting for action from the Atlanta Development Authority.

Our home site in East Point was a great meeting point for a wide cross section of Atlanta society. On market day, doctors, lawyers, civil servants, teachers, people of varied nationalities, young and old, began to meet, share stories and recipes and generally learn about people with whom they would not otherwise socialize. We believed the centrality of the Old Fourth Ward, the proximity of Wheat Street and Ebenezer Baptist Churches, the neighborhood’s relatively stable population of older citizens and the existing Auburn Avenue/Wheat Street business districts would provide a complementary template for community-building. We wanted to demonstrate that urban farming could exist side-by-side with skyscrapers, community businesses and inner-city neighborhoods. The farm would enhance the health and lives of everyone who visited or lived nearby.

Forming a collaborative partnership with the Wheat Street Charitable Foundation was the essence of our pitch and negotiation. Project benefits for the collaboration included:

Transforming an area affected by urban blight into a unique city amenity

Job creation

Educational opportunities and enhancement of community health

Increased supply of quality food

Positive environmental impact and significant waste disposal savings by using green waste for compost

Increased traffic to support area businesses

Development of a unique social/recreational gathering place

Convenient, accessible market focused on local products and

Participation in growing Atlanta’s agro and experiential tourism industries.

The Wheat Street Charitable Foundation insisted that their charter was to develop new housing on the site. We had to convince them of the benefits that the farm would bring to the Foundation. Rather than having an open and empty 11-acre space, the creation of an urban farm would significantly improve the neighborhood. Leasing the land to TLW would increase cash flow for the Foundation and improve the property. The Wheat Street Garden Farm was an opportunity for the Foundation to leverage the social, educational, and environmental aspects of the project to support other programs. The farm would be a model for healthy, sustainable communities.

After almost a year of negotiation, we broke ground at Wheat Street on 5 December 2010, a very cold day in Atlanta. About 250 people attended the dedication. The Arthur M. Blank Foundation gave us a (literally) big check for $50,000 as part of the program. We had also received $100,000 from the Cox Foundation. This was our working capital.

The farm design was conceived one rainy night, while I stood alone on the site under a full moon. Demolition of the apartment complex had left concrete slabs that were the footprints of the old Wheat Street Garden housing complex. Rather than removing the slabs, I decided to install raised beds. By doing this, we were able to demonstrate the efficacy of raised bed growing, which allows greater control of the soil and weeds. It is also easier for seniors, because it requires less effort in bed preparation. We did remove one parking lot and had other land onsite designated for in-ground growing. Other design elements included a greenhouse, aquaponics, community garden space, a composting facility, a market and event pavilion and, of course, space for flower, herb, vegetable and fruit production.

Eugene Cooke returned from varying enterprises to again work with TLW as Farm Operations Director and was responsible for implementing the vision. A visual artist by training, Eugene’s aesthetic added immeasurably to the overall design.

I always tell people the first thing they should do in creating and building a garden or farmscape is to plant fruit trees. Trees are easy to maintain and generate long-term income. By March of 2011, we had planted over 100 fruit trees at the Wheat Street Farm, including apples, pears, plums, peaches and persimmons. Blackberry and raspberry vines sprouted. Collard greens, mustard greens and broccoli were being harvested from the fields and sold at our new on-farm market. This gave us the opportunity to sell at our downtown location, in addition to the continued sales in East Point. We collected compostable materials from local markets, restaurants and coffee shops. Neighbors brought kitchen scraps to add to the ever-increasing compost pile. Community residents bought starter plants from the greenhouse, and we created a community garden for seniors. It was a good start.

Truly Living Well became the largest urban farm in the metropolitan area. The terms of our agreement with Wheat Street Charitable Foundation were quite steep. We paid about $50,000 per year in lease payments. No farmer in his right mind would pay what we agreed to pay. But I thought it would be a great investment in the future of urban agriculture in Atlanta. We could be an example of the efficacy of growing food in the city. We could be seen from the highway, in the shadow of the downtown skyscrapers. I loved being able to say that. More importantly, I knew that our success would benefit the entire local food movement. Truly Living Well demonstrated proof of concept for urban agriculture in Atlanta.

Although TLW was the largest urban farm in Metro Atlanta, it was our education and outreach programs for youth and adults that distinguished us from other urban agricultural organizations in the area. My son, Kamal, wrote the Urban Oasis Beginner Farmer Training, Internship and Incubation Program for submission to the USDA, which was funded in 2011 at nearly $1 million, spread over three years. To this day, it remains the largest single grant ever received by TLW. He was assisted in drafting the proposal through collaboration with EcoVentures International, a Washington, D.C. based firm. The prototype for the program was the work we did in the ten-week program Kamal administered with Historic Westside Gardens in 2009.

The development and management of the Urban Oasis Program provided the framework for the expansion of a sustainable infrastructure that provided employment through the production of affordable, locally grown foods. The internship experience and Urban Oasis Incubation Program provided the hands-on learning, mentoring and business skills acquisition needed to launch successful urban farming enterprises.

Ras Kofi Kwayana was hired to be our master trainer. His background was teaching. He had a wonderful facility in relating to the students. There were twenty-five trainees in each 6-month cohort. They learned urban agriculture and technical business skills from a curriculum initially created by HABESHA, Inc. and further developed by TLW. Practical implementation of the classroom work took place on Truly Living Well sites in East Point and Southwest Atlanta. As part of their education, trainees received nutritional information and healthy lunches, made primarily from vegetables grown at the farm. Trainees gained hands-on experience in agricultural production, ultimately enabling them to plan and develop their own gardens.

In addition to an in-depth agricultural education, students learned the importance of planning, execution, business math, economics, budgeting, marketing, basic cost-benefit analysis, time management, plan presentation, negotiation and many other transferable skills. The students demonstrated their skills in a final project that involved writing a business plan for a plot of land, executing the plan and selling their products at market. The trainees also initiated personal and/or business plans, whether it was for starting a small garden market or preparing for the job of their choice.

Truly Living Well’s long-term goals for the Urban Oasis Beginner Farmer Enterprise Training, Internship and Incubation program were to:

Increase economic prosperity for low-income communities through viable self-employment and employment opportunities in urban farming;

Increase access to and consumption of healthy, local food for all income levels in Metro Atlanta;

Implement a comprehensive beginning urban farmer training program and support network that results in increased production of healthy food without the use of petrochemicals;

Develop and use accessible business models and tools for beginner urban farmers; and

Increase food literacy, particularly awareness of how food and food choices impact health.

The first cohort of students from the Urban Growers Training Program graduated In October 2012. Eighty-one percent of the 31 graduates were subsequently employed, either as self-employed farmers or as employees of TLW and other farming or environmental organizations, including Atlanta Food & Farm, Captain Planet Foundation, East Lake Farmers Market, Global Growers Network and Southeastern Horticulture Society.

Aside from being one of the few professional agricultural training programs in the metro area, the Urban Growers Training Program was distinct, in that it offered students the opportunity to see the practical application of natural materials and farming techniques in a variety of urban settings. Another distinction was the curriculum's modular content, which made the program adaptable for different audiences. In this way, TLW was able to collaborate with community organizations serving a variety of constituents, including homeless veterans, juvenile offenders and high-school dropouts. Our collaborations provided tangible job skills training, as well as important life skills.

In 2011-2012, for example, TLW:

Trained a group of homeless individuals in how to create and maintain a large roof garden at the Peachtree and Pine shelter where they were living;

Worked with teens from Tri-Cities High School, Blackstone Academy Charter School and

Benjamin E. Mays High School to introduce them to alternative careers in agriculture; and

Provided instruction and practical on-site farming experience to nearly a dozen teens identified by their counselors as being in danger of dropping out of school and losing their way in life.

Through these experiences, TLW has seen firsthand how working with the soil and learning valuable life skills can lift individuals' self-esteem, reconnect them with their community and set them on a positive path for the future.

TLW initiated its Growing Families Project in 2016. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation funded the project in the amount of $500,000 over 3 years. Growing Families used urban agriculture as a transformational tool to improve economic and health outcomes for women and children. Adults learned fundamental practices in urban agriculture through participation in a 12-week training program. The mothers spent four hours in an interactive classroom setting to learn the science and principles of natural agriculture, and eight hours in experiential learning at the TLW farm sites. Children learned age-appropriate gardening techniques to support family interaction in producing food.

Families learned to make better food choices that improved their health outcomes. A registered dietitian incorporated nutrition education and food prep training around plant-based diets into the curriculum for women and children. During the program, families received two additional servings of fresh produce a day, to promote healthy food consumption and address food insecurity.

Amakiasu Howze directed the Summer Camp. She is a remarkable educator, who has great empathy with children. Her genuine respect for children instills a sense of equality and confidence in their own capacities. Under Amakiasu’s tutelage, the children were fully engaged in the learning process. Using elements of organic farming, environmental stewardship, health, wellness and self-discovery, Amakiasu created a transformative experience for children at the Wheat Street Gardens Summer Camp.

Campers demonstrated improved self-discipline, while engaging in critical thinking and team building. Fun activities reinforced their use of math, science and creativity. The children gained measurable health outcomes from the physical activity of gardening, swimming and creative movement, combined with eating healthy food and learning to make healthy food choices.

Food production became the platform or the plate upon which the programs were served. TLW became a plug-n-play organization. I could design a program for just about anybody around whatever his or her interests were and plug it into the new paradigm of urban agriculture. The menu included after-school programs, food coops, summer camps, the Urban Growers and Young Growers Programs, Boot Camps, agritourism and edutourism. Children attended farm trips with school groups and participated in farm activities. We shared the importance of agriculture from a very practical point of view with everyone we could reach. The gardens were a unifying force within the community. We grew food. We grew people. We grew community.

It was incredibly gratifying to look around and see that we were actually DOING THE WORK that had been at the heart of my earlier studies. I had absorbed the spirit and practice of men and women who built the post-colonial world. After studying the work of those revolutionaries, I had the opportunity to see many of the countries that had gained their independence and witness firsthand some of the successes and failures of both colonialism and independence.

We were engaged in building a nation. By growing people, we were helping people reach new dimensions. We were introducing people to a greater variety of fresh foods. Having fresh food, grown in the community, to put on people's tables, is a wonderful thing. The 360-degree process of urban agriculture improves nutrition and health, beautifies the community, raises the property values, creates green spaces that clean the air, provides a meeting place for people and creates jobs. Through growing food, people are learning new skills that are transferrable to other professions and other areas of their lives.

We had folk who loved coming out to the garden, just to see it and feel it. They talked about the peaceful energy of the garden space. In this society and in most societies, holidays are always associated with food. This is when people come together, and they come together around food. Halloween is primarily candy— they should forget that stuff. But Thanksgiving, Chanukah, Christmas, Kwanza, New Year's, Easter, Memorial Day and the Fourth of July—you name a holiday or any time when people come together— there is always food associated with the occasion. And I think that's important. It's tradition, its history, and TLW positioned itself to play a part in maintaining those traditions. We provided a place for people to come together. At a minimum, one or two times a month, there were food-centered events at the farm.

Market day at the farm was Friday afternoon. I would set up chairs under a tree across the parking lot from the market pavilion. People knew I would be there and frequently would come over to talk with me. It was an opportunity to talk about urban agriculture and any other subject folks wanted to raise. It was a good way to introduce and welcome people to the urban ag community. The discussions covered the gamut of community issues, program problems and personal concerns. This was time I set aside as community outreach, and I thoroughly enjoyed the engagement.

In 2005, a group of interested citizens and organizations began a dialogue to create a more sustainable food system for Metro Atlanta, resulting in the creation of the Atlanta Local Food Initiative (ALFI). Three women led the effort. Peggy Barlett is an Emory University Professor, and a very early proponent of environmental sustainability in academia. Barbara Petit was a local chef and a major food activist. She was President of Georgia Organics and the first Executive Director of the Atlanta Local Food Initiative. Alice Rolls was and is the Executive Director of Georgia Organics.

The Atlanta Local Food Initiative envisioned a transformed food system, in which every citizen of Atlanta would have access to safe, nutritious and affordable food, grown by a thriving network of sustainable farms and gardens. A greener Metro Atlanta that embraced a sustainable, local food system would enhance human health, promote environmental renewal, foster local economies and link rural and urban communities.

I began working with ALFI in late 2006. It was a very reachable group, yet I was the only Black person at the table. We decided to produce a manifesto on urban agriculture that expressed the collected wisdom of the group. One of the definitive lessons of that experience was the difficulty of attempting to have a group of 25-30 rotating people wordsmith a document. Finally, we appointed a steering committee to draft the 17-page document entitled, A Plan for Atlanta’s Sustainable Food Future, that was edited by the entire group.

After two years of work, the manuscript was finally published in 2008. Although it took considerable time to produce, the plan was strong and has stood the test of time. The eight goals in the plan are well thought through. Truly Living Well has been instrumental in implementation of the goals through its own organizational commitments.

ALFI Goals

Supply

Increase sustainable farms, farmers and food production in Metro Atlanta.

Expand the number of community gardens.

Encourage backyard gardens, edible landscaping and urban orchards.

Consumption

Launch Farm-to-School programs (gardens, cafeteria food and curricula).

Promote consumers’ cooking skills for simple dishes made from fresh, locally grown foods.

Develop local purchasing guidelines and incentives for governments, hospitals, and Atlanta institutions.

Access

Increase local, fresh food availability in underserved neighborhoods.

Increase and promote local food in grocery stores, farmers’ markets, restaurants, and other food outlets.

The next phase in ALFI’s work was to educate policy makers and community leaders to integrate the visioning and goals into sustainability plans and initiatives. One of our greatest successes was having the ALFI plan used as a guideline for the food component of Mayor Kasim Reed’s sustainability initiative.

ALFI worked with the Emory Turner Environmental Law Clinic to draft and propose an urban agriculture ordinance for Atlanta. The Clinic provides important pro bono legal representation to individuals, community groups and nonprofit organizations that seek to protect and restore the natural environment for the benefit of the public. Through its work, the clinic offers Emory students an intense, hands-on introduction to environmental law and trains the next generation of environmental attorneys. Led by Mindy Goldstein, the Clinic drafted a potential urban agriculture ordinance for Atlanta.

The problem was that the City of Atlanta had no inner-city zoning ordinances that addressed growing food. Technically, farming in the city was illegal. We live in a system that requires citizens to get permission to do just about everything. This allows the government to collect fees. Although unlikely, if your neighbor objected to bees pollinating the vegetable garden in your yard, the neighbor could call code enforcement and have them write you a ticket because gardens are not in the zoning ordinance. Absurd, I know!

The draft ordinance prepared by the Emory Turner Environmental Law Clinic was presented to ALFI at one of the monthly meetings. I strenuously objected to the process, because farmers had not been included or consulted in the course of drafting the legislation. At that time, a majority of the inner-city farmers were Black. ALFI’s membership was primarily White. Therefore, my objections were received and perceived as a racial issue. The discussion became quite heated, until Susan Pavlin, a tall White woman with blond hair and blue eyes, stood up and boldly declared: “Rashid is right. You cannot put together anything about farms and farming without including farmers in the process.” I will forever respect her for that proclamation.

Subsequently the issues were resolved, farmer input was included, and the result was the most progressive zoning ordinance in the country at that time. Farming was permitted in every sector of the city, with the caveat that former industrial zones would require soil tests for toxins and pollutants before farming could commence. A similar community exercise helped resolve issues around location and rules for farmers’ markets.

Georgia Organics also helped to make significant inroads in building Atlanta’s local food economy. Georgia Organics is a statewide nonprofit that supports the efforts of organic and natural farmers and educates the public about organics and nutrition. Alice Rolls, one of ALFI’s founders, is the Executive Director. I served on the Board of Directors of Georgia Organics from 2008-2014 and as chair from 2012-2013. My leadership marked a clear delineation in the organization’s becoming more racially diverse and inclusive in its strategic direction and outreach. The Georgia Organics Annual Conference now has a very racially diverse mix of attendees, possibly more than any statewide sustainable agriculture conference in the country. I was proud to be honored for my work and leadership as the recipient of the Georgia Organics 2017 Land Stewardship Award.

In 2010, I started appearing on a radio program on the Atlanta-based independent community radio station - WRFG, Radio Free Georgia – that also affiliates with the national progressive Pacifica Network. Heather Gray is a researcher, journalist and producer of the “Just Peace” program on WRFG. Once a month, we explored virtually all aspects of agriculture and its history, with a focus on organic production. This included information about techniques and strategies for healthy gardening, without the use of chemicals, which destroy the soil and human health.

Beyond techniques for gardening, we also explored agriculture, politics and history from a worldwide cultural perspective. Along that line, we also discussed food politics and how food can be used to control people, and how the lack of food can and does lead to war. Our discussions included the efforts by US corporate interests to control food production, distribution and exchange, and the concerted efforts to suppress the historic independence of small farmers and their communities throughout the world.

On the monthly radio show, people called in and joined the conversation. They would ask insightful questions about gardening techniques, as well as food politics. ‘Just Peace’ and my monthly interviews continue to be inspirational for me. Program producers and listeners express they are also inspired by the topics covered in the interviews.

In the summer of 2011, I made one of the better decisions of my career. Truly Living Well had established proof of concept. We had demonstrated that Atlanta could support an urban farm in the middle of the city. It had not been done before, and despite the critics and cynics, we had assembled the physical infrastructure and created an admiral showcase that many farmers and organizations emulated. The organization had grown. Truly Living Well had created 35 livable wage (seasonal and permanent) jobs in urban agriculture. In addition, entrepreneurs in our grower training program developed agri-businesses in the Atlanta area. We bought locally and circulated dollars within the metropolitan economy. It was time to consolidate and formalize our administrative infrastructure.

A mutual friend introduced me to Carol Hunter, suggesting she could help organize the administrative work that TLW required. I contracted with Carol for her to conduct an evaluation and suggest a course of action. She accomplished the study with great aplomb. After reading her report, I congratulated her on the good work and asked her to implement the content. That was a great decision.

Carol became the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO). She managed all activities associated with human resources. She supported fundraising efforts by writing proposals and led the grant writing team. She created the Personnel and Board Manuals. She kept minutes and records from all Board meetings. Carol headed up all of our educational efforts, both creating and managing programs. As the CAO, Carol interfaced with all stakeholders to promote and develop an environment of continual improvement in every aspect of TLW’s products and services.

By 2012, we had made tremendous progress with implementing our business plan. It was time to present a vision for the future of Truly Living Well. I was suffering blank page writer’s block trying to figure out what to put on paper. One day I was riding Amtrak’s Surfliner from San Diego to Los Angeles, after having visited my sisters. On the train ride to L.A., I came to the realization that I did not need to come up with anything new. Rather than writing about what we were going to do at Truly Living Well, I realized the story to share is what we were doing. Thus, the title of a twenty-page document:

Doing the Work of Urban Agriculture

The Truly Living Well Center: A Model for Sustainable Local Food Systems

After six years of practical experience, we were able to codify and articulate what we were doing and achieving through our work. We envisioned ourselves as a national leader in natural urban agriculture. We demonstrated sustainable and economically viable solutions for helping people to eat and live better. We recognized that our work transformed both people and places.

The transformative power of the work that we did at Truly Living Well confirmed the potential of a renewed paradigm—the local food economy. Our mission was to grow better communities by connecting people with their food and the land through education, training and demonstration of economic success in natural urban agriculture. Much of the following text comes straight from the pages of Doing the Work, which aptly described what TLW was and is all about:

Eating well is a right for all, not a privilege for the few. Sustainable local food systems establish perpetual cycles of productivity. They make healthy food accessible to all, enhance the natural environment and create employment. The TLW model of natural urban agriculture combines the economic vitality of city life with the benefits of being close to nature and creating communities that are truly living well.

Truly Living Well thrives because we understand that natural urban agriculture is about more than growing food in small spaces. Connecting people with the land builds positive personal relationships and establishes an ethic of community and environmental stewardship.

Our guiding principles encourage vibrant and manageable growth:

We emulate nature

We educate

We prioritize partners’ interests and input

We keep our values central and simple:

Superior quality

Integrity and honesty

Diversity and teamwork

Creativity and imagination

A positive response from the community, fellow nonprofits, educational institutions, philanthropic organizations and others help to fuel the growth of Truly Living Well. Widespread support affirms our approach and guiding principles. The strength of this foundation assures progress toward the goals and objectives for the next three to five years.

Goal 1. Solidify our base to achieve economic self-sufficiency

Objectives:

Purchase and develop a 15 to 25-acre permanent home base and training facility for the Truly Living Well Center for Natural Urban Agriculture

Strengthen our human capacity to manage and support growth

Expand and diversify our revenue base

Create an effective method to measure and evaluate progress

Goal 2. Strengthen the social and political foundation for urban agriculture

Objectives:

Strengthen public, private and nonprofit alliances

Improve the regulatory and legal environment for urban agriculture

Increase resource availability for urban agriculture

Increase consumer awareness of the local food system

Goal 3. Increase access to natural, locally grown food

Objectives:

Expand Truly Living Well Center as a food hub

Increase production, distribution and exchange of local food

Educate and train a multitude of urban agricultural entrepreneurs

Increase urban agriculture-based employment

Sustain and expand community outreach services

Goal 4: Raise $5,000,000 in investment over the next three to five years to accomplish these goals:

Objectives:

Develop fundraising and capital campaign initiatives

Identify financial benefactors

Expand relations with foundations

We worked hard to achieve these goals. We expanded as opportunity arose, following nature’s example of expansion only when and where growth is sustainable. Patience was essential! We started small and mastered one thing before beginning another. Although pushing boundaries, we understood that taking on too much at once would likely lead to being overwhelmed and unproductive.

Our Board of Directors took on these goals as part of our strategic plans. Board development was the one area of our work that I found most difficult, and in which I was least successful. When we disbanded the LLC and incorporated the nonprofit, it meant that control and governance of TLW would be handed over to an “external” board of directors. I understood this reality. Throughout my tenure, I had the latitude to recruit and invite men and women to join the board that I thought would help our efforts. I was recruiting people to help run TLW, and these same people could potentially fire me. It was, however, necessary and important.

I was taught there are two types of boards, each requiring different skills and expertise. The first is a working board, whose members raise money, develop contacts for the organization and act as ambassadors to the community. The second type is a governing board. The governance role involves protecting the public interest, being a fiduciary, selecting the executive director and assessing his or her performance, ensuring compliance with legal and tax requirements and evaluating the organization's work. Nonprofit organizations are accountable to the donors, funders, volunteers, program recipients and the public.

Financing a nonprofit organization is the principal challenge of the CEO and the board, particularly one with a mission that people don’t completely understand. I had personal financial challenges in building TLW, like the times I had no heat, water or electricity. I always had food, because I was growing it. Nothing is more dispiriting than cash flow issues that lead to missing payroll, which means being unable to pay employees for their hard work, done in good faith. There were times when missing payroll resulted from cash flow issues, such as the unpredictable timing of grant allocations.

I had Board members who quit because they thought it was unconscionable to not pay employees in a timely manner. I took a deep breath there, because I got very angry. As a Board member, their job was to help me raise money, so I would not have to face that situation. I thought it was unconscionable for a Board member to stand back and basically tell me to shut down the business because of cash flow issues. My answer was no. I was not going to shut down.

Nonprofit finances were a particularly great problem for urban agricultural organizations. I had to bring to people the understanding that all agriculture in this country, at every single level, is subsidized. People visit a farmer’s market and think they are paying more out of pocket than they do at Kroger or Publix. The difference is that food at Publix has been subsidized. California is the richest agricultural region in the history of the world, and feeds not only other states, but other countries as well. Data from the USDA Economic Research Service show that California’s plant-based agricultural exports grew from 16% to 20% of American agricultural exports between 2000 and 2017.

The history of California is the history of water. Have you ever seen the movie, China Town? Fundamentally a true story, China Town is the history of California’s water. It is water that has been paid for by the taxpayers of America. If those farmers had to pay for the water out of their own pockets, there never would have been any agriculture in California. Agriculture at every level is supported.

Education is the same way. It is subsidized and supported. There are no schools that can run on the tuition they charge. Many students pay their tuition with state and federal grants and loans. Post-secondary institutions seek grantors and donors. Professors write grants to support their research; they have to go out and get their own money. Alumni donate money to their alma maters. The very best schools in this country have the largest endowments, which they are able to draw upon to manage the institutions.

My work was both agriculture and education. We needed support. We were able to increase our earned income to 25-30% of total revenues. My goal was to get income earned from programs and sales up to 50-60%. The rest of the operating capital had to come from donations and grants to support our education and training programs.

The early TLW Boards were comprised of friends and individuals who supported me. Not everyone understood the zeal with which I approached the work of urban agriculture. Over time, as folk saw the progress and success that we achieved, many became believers, and certainly champions. As we moved forward, the board participated in developing strategic plans that further reflected and detailed the goals and objectives. I was eventually able to recruit men and women, Black and White, rich and poor, who were committed to Truly Living Well. All of those members enthusiastically and dutifully supported the mission, vision and goals of the organization. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to work with them.

*

“Even after all this time

The Sun never says to the Earth,

‘You owe me.’

Look what happens with a love like that.

It lights the whole sky.”

Hafiz

Chapter 23

Truly Living Well 3.0

In the spring of 2015, I received a call from the Board President of the Wheat Street Charitable Foundation, inviting me to meet with her and the Board. Over the years, we often met to give updates, negotiate terms of engagement or to request amendments to our agreements. Carol Hunter, our Chief Administrative Officer, and Imam Plemon El-Amin, the TLW Board Treasurer, accompanied me. In addition to the usual Wheat Street representatives, two people attended the meeting, representing The Integral Group LLC.

Integral, founded by Egbert Perry, had a solid reputation for bringing innovative community, housing and infrastructure solutions to strengthen and revitalize urban communities. They developed Centennial Place, the nation’s first holistic community revitalization project. Centennial integrated mixed-income rental housing and home ownership, including an early childhood development center, a K-12 STEAM public school, a family recreation center, and health & wellness YMCA, along with family support services.

The lease we had for Wheat Street Gardens was only for three years, and we also had the ability to renew the lease on an annual basis. In the spring of 2015, we had used the site for four and a half years. At the June meeting, we were told that the lease would not be renewed, and we were given one year to vacate the space. The Foundation Directors were ready to return to their original charter to build housing. The plan was for Integral Group to develop housing on the site. An urban farm was not part of that plan. Knowing how important the farm site was to Truly Living Well, the folk from Integral brought with them a plot map of a potential site to which TLW could move if it proved satisfactory. I was impressed and grateful that Integral and Wheat Street Charitable Foundation had taken steps to prevent a loss of the community benefits of urban agriculture and Truly Living Well.

I immediately sensed something special was about to happen. The site being offered was in the West End area of Southwest Atlanta, on the land where Harris Homes Apartments had previously stood. The projects had been torn down in preparation for the Olympics in 1996. On the Harris Homes site, Integral had developed a mixed-income neighborhood, similar to Centennial Place, called Collegetown, directly across Lowery Blvd from the Morehouse Stadium. At the far western edge of the site, there were approximately ten acres of land yet undeveloped, likely because of the topography. The Atlanta Housing Authority owned all of the land, and Integral maintained development rights.

When I went to view the property, I was exhilarated by the possibilities. Before us was an opportunity to own our own land, in the middle of the rapidly gentrifying Black community. They offered us three plus acres of flatland at the bottom of a hill, which we would initially lease, but eventually would own, at a very reasonable price. We negotiated a lease for another three-plus acres of hillside we that we could use but would not own. Complicating the transaction were the tripartite political machinations between Integral, the City of Atlanta and the Atlanta Housing Authority.

In September 2015, I wrote a letter to Trish O’Connell, Vice President of Real Estate Development for the Atlanta Housing Authority. In it, I said that TLW welcomed an opportunity to collaborate with Integral and the Atlanta Housing Authority to establish an urban farming oasis in Collegetown. TLW sought to establish a permanent base for its operations. We were interested in the 3-acre Collegetown property and would like to first obtain an access agreement and subsequently purchase the property, currently owned by the Atlanta Housing Authority.

We also requested a letter from Integral stating they agreed with our proposal and supported the project. Integral signed off on that portion of the deal. This letter of support was submitted to the Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA). It enabled TLW to continue the approval process with the AHA for the Collegetown Urban Agriculture Education and Training Center.

The Collegetown location was ideal for Truly Living Well. The area around the farm site is designated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a "food desert," meaning an area with limited or little access to fresh food. In addition, the area is within walking distance from the Atlanta Beltline and home to our core constituency and ideal partners.

Loss of land access and land ownership is one of the major issues facing Black people in America. The amount of land owned and controlled by Black people has continued to decrease from its height of 18 million acres, reached in 1910. The problem in the inner city is heightened because landowners and developers are looking for the highest paying and best use of land. Urban agriculture is not considered the best use. TLW was presented with an historic opportunity, but the issue was how to finance the transaction.

By 2014, most of my time was engaged in fundraising—dialing for dollars. My to-do list on any given day was much the same as it was on any other day. Emails. Meetings. Phone calls. Where to find money to cover payroll! Those were the fields that I plowed.

I cultivated relationships through emails and meetings. I would travel up and down the rows of emails, turn them over, test the quality of the soil, examine them for telltale signs of life: earthworms, roly-polies, lizards. I inhaled the aromas, hoping for the full, rich fragrance of nutritious humus, food for my crops. I would toss out hundreds of communications that amounted to chemical additives—pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers—before I chanced upon the rare real deal. Good quality, natural, soil-enriching compost was exceptionally hard to find in my mailbox. Meetings were the same: the perpetual probe for the right combination of ideas, words and people that would propel us beyond the day-to-day search for sustenance.

I asked myself, if I’m a farmer, why do I feel so much like a hunter-gatherer? Isn’t agriculture supposed to make food provision easier? It shouldn’t be this hard-to-find money to feed people. Everybody eats. Many folks want to help poor folks eat, and they do so. My perpetual task was to find those folks with whom I could create synergy among the emails and meetings.

A typical work day would go something like this: After breakfast (which, by the way, does not originate on our farm), I’m off to one of our sites. A visit to the fields is redemptive. The plants grow on, dependably oblivious to the politics that surrounds their existence. Similarly, a delightful gaggle of children is dismounting from a yellow school bus as I approach. Eager to escape the firm reins of their keepers, the children are ready to mingle their innocence with that of the plants and flowers in the field.

***

To order a signed copy of Growing Out Loud and read the rest of the story, visit https://www.thenurigroup.com/book