It’s Personal

FOR THE LOVE OF LITERATURE

BY KHADIJA POUNSEL

I have known both of you all your lives, have carried your Daddy in my arms and on my shoulders, kissed and spanked him and watched him learn to walk. I don’t know if you’ve known anybody from that far back; if you’ve loved anybody that long, first as an infant, then as a child, then as a man, you gain a strange perspective on time and human pain and effort. Other people cannot see what I see whenever I look into your father’s face, for behind your father’s face as it is today are all those other faces which where his. Let him laugh and I see a cellar your father does not remember and a house he does not remember and I hear in his present laughter, his laughter as a child. Let him curse and I remember him falling down the cellar steps and howling, and I remember, with pain, his tears, which my hand or your grandmother’s so easily wiped away (Baldwin, pages 4-5).

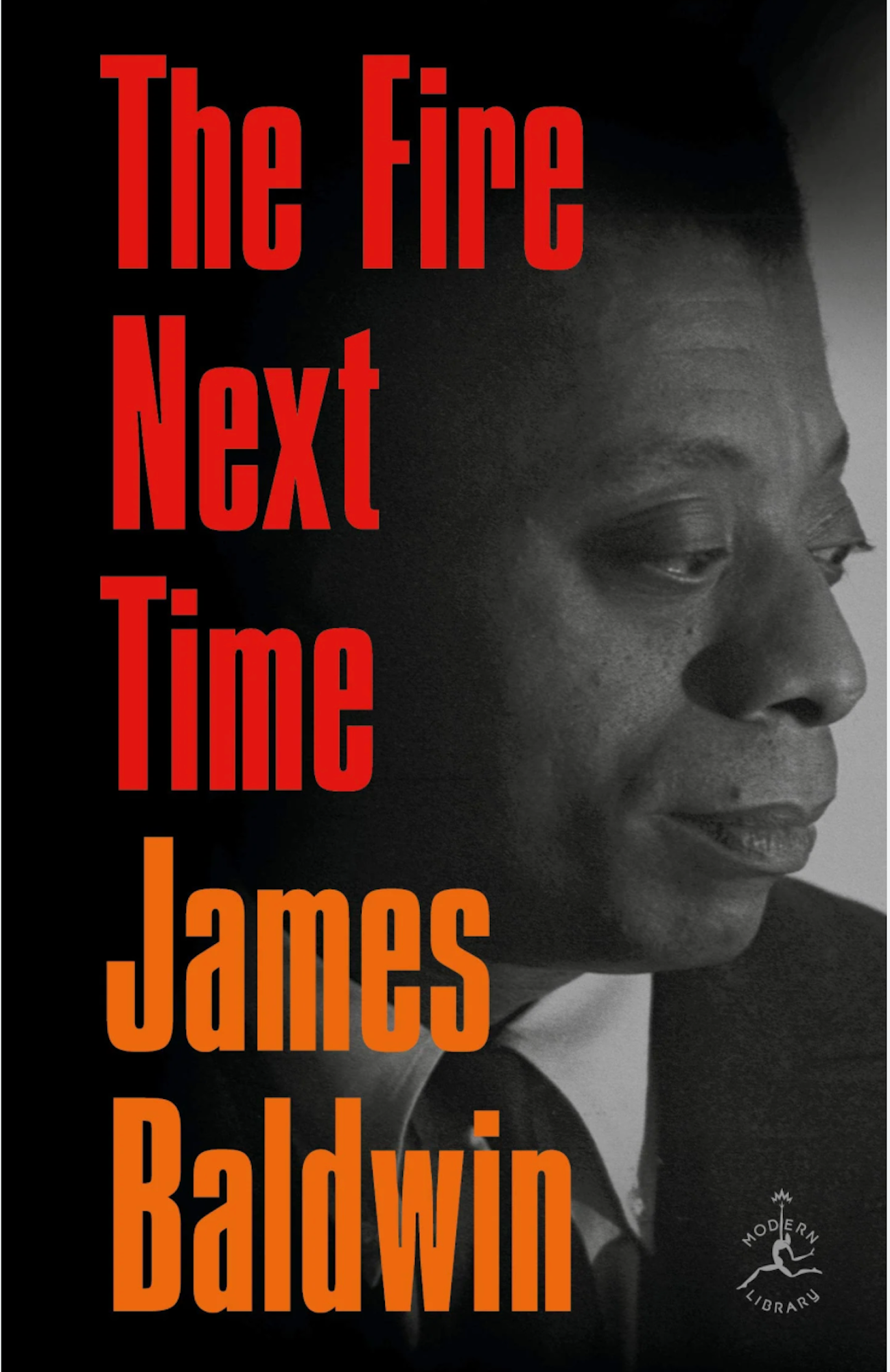

These words by literary great, James Baldwin, in a letter to his nephew published in the book, The Fire Next Time, seem a fitting site to explore within this issue’s theme of “Legacy.” This portion is not the frank observations and commentary around historic or mid-20th century societal ills that come in the letter too. Somehow, for me, these words feel old and deep and shared; they are the kind of sentiments we collectively have carried from place to place across our generations.

However, undoubtedly in this excerpt, there is yet a historian at work.

By saying, “I have known both of you all your lives, have carried your Daddy in my arms and on my shoulders, kissed and spanked him and watched him learn to walk” (page 4), Baldwin acts as a kind of family historian.

Baldwin goes on to write:

Well, you were born, here you came, something like fifteen years ago; and though your father and mother and grandmother, looking about the streets through which they brought you, had every reason to be heavyhearted, yet they were not. For here you were, Big James, named for me—you were a big baby, I was not—here you were: to be loved. To be loved, baby, hard, at once, and forever, to strengthen you against the loveless world. Remember that: I know how black it looks today for you. It looked bad that day, too; yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other none of us would have survived (page 7).

By highlighting the collective category of family, Baldwin gives a history that not only features a roll call, but key character traits and relationships.

When he says, “… here you were: to be loved. To be loved, baby, hard, at once, and forever, to strengthen you against the loveless world,” Baldwin shares the family’s deliberate, intentional commitment to strongly love his nephew in order to fortify him for life in a harsh society. Surely, many can identify with the approach—as giver or receiver; believing too that “… If we had not loved each other none of us would have survived” (page 7).

Certainly, the witness of having survived because of love is the shared testimony of many in our numbers, across time. And so is the charge, either given or received, even yet still:

“And now you must survive because we love you, and for the sake of your children and your children’s children” (page 7).

Loving Literature,

Khadija Pounsel