Treasures of the African Diaspora

BY ZAKIYYAH ALI

Cathay Williams & Dr. Daisy Century:

A Black Female Buffalo Soldier & Her Historian

Part One: Cathay Williams

Cathay Williams c. 1868

Can you imagine being enslaved during the Civil War in America? Maybe you can imagine being contraband, a name put on African Americans during the Civil War who were taken or joined with the Union Army. Even bolder is the visualization of being a buffalo soldier during the late 1800s. One woman, Cathay Williams, didn’t have to imagine or visualize these things. She lived them all.

The amazing and little-told story and history of the only female Buffalo Soldier is one we all should know and share. Born in 1844 to an enslaved mother and free father in Independence, Missouri, Cathay learned to read and write from her father. During her youth she worked in the “big house” as a cook and maid, honing skills that would serve her later.

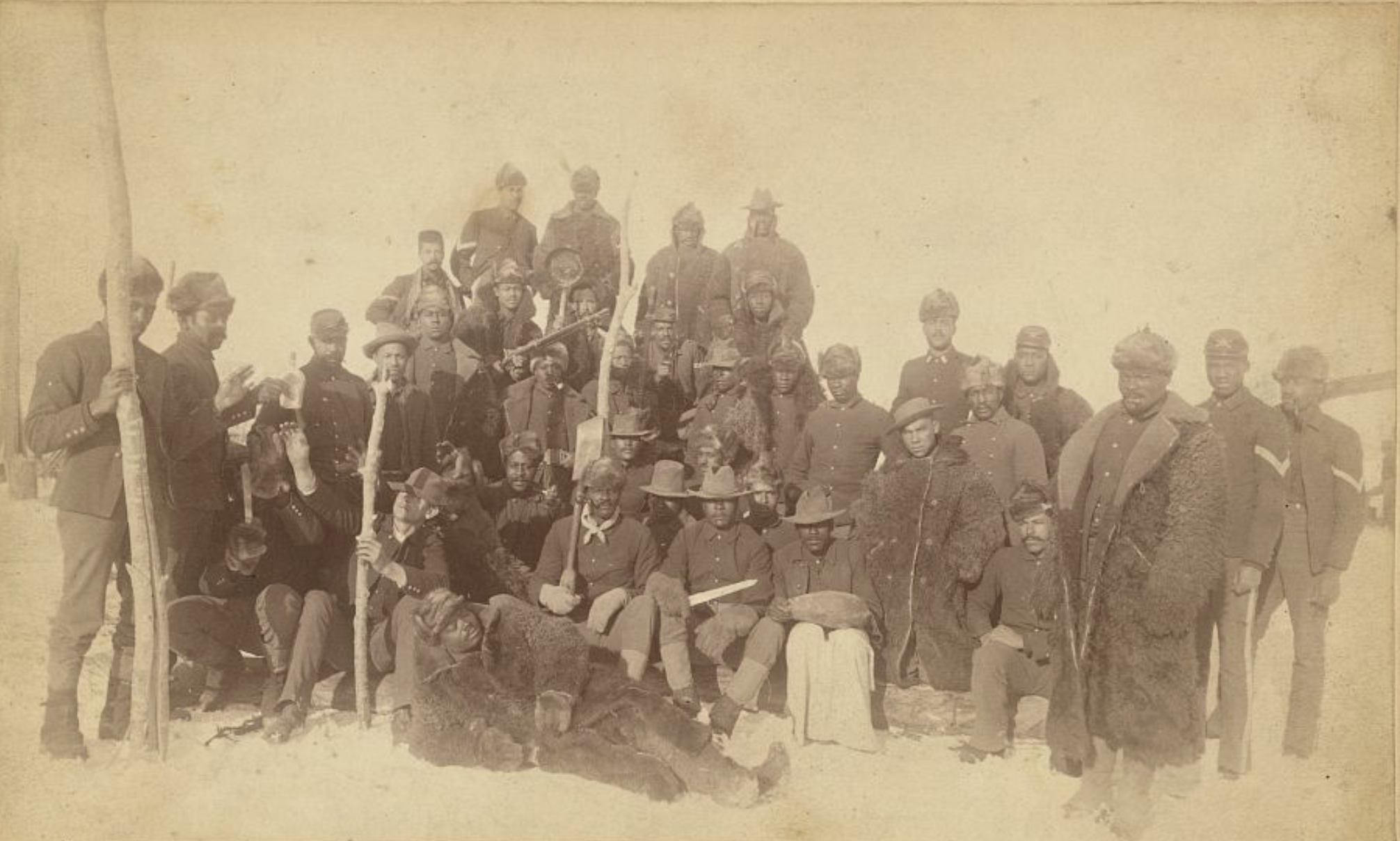

The Union Army recruited a significant number of Buffalo Soldiers from the ranks of former enslaved men designated as contraband. Their units were assigned tasks that no one else wanted to do, such as digging burial grounds, putting up fences, scouting and fighting Native Americans. Genuine frontiersmen, Buffalo Soldiers marched all over the West. On one of their journeys, they walked from Jefferson City, Missouri to New Mexico on the Santa Fe Trail, covering five states and some 1,200 miles. Native Americans named the units based upon the men’s wooly hair and their wearing buffalo hides. All the Native American nations knew the Buffalo Soldiers—the Creek, the Cherokee, Choctaw, the Seminoles and others. The army put the soldiers in direct conflict with Native American nations.

Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana] / Chr. Barthelmess, photographer, Fort Keogh, Montana. Published 1890. Source: Library of Congress

We tend to forget that a lot of Native Americans at that time were dark-skinned folks. When Buffalo Soldiers encountered them, some of the men were like, “Wait a minute, you look like my aunt and my grandma!” And of course, many were looking for female companionship. I imagine that facing people who looked and cooked like them gave the soldiers pause. “Wait a minute; this is a little bit too much,” they might have said. Smelling rabbit cooking with barbecue sauce, they may have been like, “Hold up, Homie, let me get some of that.” Not only barbecued rabbit, but buffalo ribs were on the menu as well. The real lives of Buffalo Soldiers weren’t always written about in the history books.

Buffalo Soldiers were also sent to Europe and the Caribbean, and some of them never returned to the United States. Drilling down into specific areas of history reveals little-known facts and circumstances. The history of the Buffalo Soldiers extended into the 20th Century, when among other missions, they were part of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and traveled all over the country. Most never received any recognition, because the racism within the army would not allow them advancement to higher military ranks.

I want to give a shoutout to Dr. Daisy Century for bringing this heroine to me via her cultural and historical reenactments.

Dr. Daisy Century portraying Cathay Williams

Over the past 10 years, more people have begun to recognize and celebrate Williams’ accomplishments. From Dr. Century I learned that Cathay Williams’ mother was enslaved and her father was free. At that time, a child’s status was the same as their mother’s, so Williams and her brother remained confined to the plantation. When the Union Army came through their town, she, her brother and cousin were gathered up.

Williams fulfilled the servant roles she was assigned, and also began asking her brother and cousin to teach her how to shoot. Both men said they didn’t have time or just plain didn’t want to do that, so she taught herself. She didn’t want to be out in the woods unable to defend herself, nor did she want to feel less capable than anyone around her. With practice, she learned how to shoot, and went on to ask her brother and cousin to teach her to ride a horse. Again, they refused, and again, she taught herself the skill that she wanted to learn.

Slowly, she began dressing differently, wearing riding breeches and other male-identified clothing. When the time came that Black men were able to serve in the Army, she enlisted. Enrolled as William Cathay, nobody knew that Cathay was a woman, except her brother and cousin, during the entire the time she was in the service. When she was found out, her fellow soldiers riled up and tried to come after her. Her brother and cousin defended her until she was able to escape from Army land.

As a part of the 9th and 10th Cavalry unit that she joined, Williams traveled and did everything they did. She never turned down an assignment, and whatever the men were assigned to do she did as well. Cutting down underbrush, marking trails, fighting Native Americans—she did it all, until she became sick. Predictably, the personnel at the infirmary discovered that she was a woman and she was promptly dismissed. Although she was honorably discharged from the Army, they denied her pension.

I try to imagine what it would be like becoming enslaved and having that as my first reality: a limited, controlled, probably violent existence, made worse by being separated from family. What would it be like to have this as my early beginning? Imagining myself as Cathay Williams, I see myself realizing that my dad is a free man, and he’s able to come and go. But my mom, my brother and I are here with someone that is supposed to be my ‘master’ I have to do what I’m told and stay put.” It has to be a helluvan awakening to think, “This is my life, this is what I’m destined to do.”

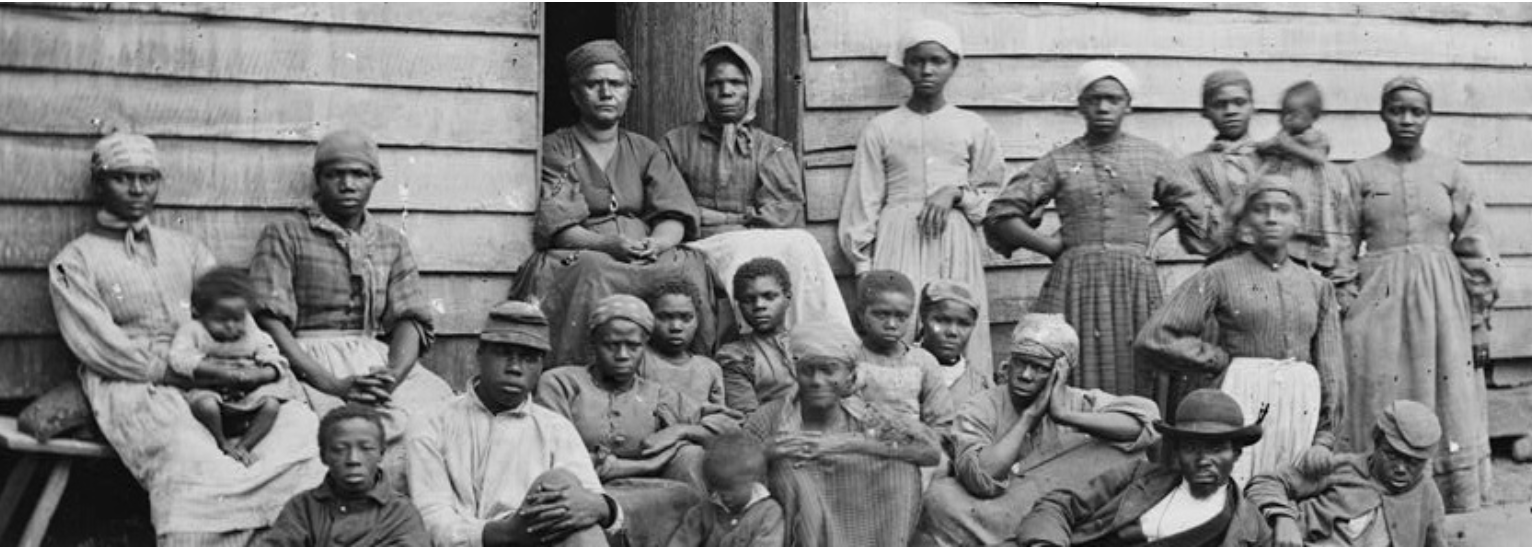

But then, “My daddy is coming to visit us and teaching me how to read, which under my current condition, is illegal, so I can’t tell anybody.” Her dad made reading and writing a game in the dirt, where he would write the letters in the sand, and if someone came, they could scrape it out real quick. “Now I’m finding out that there is another world. I don’t know if I’ll get to that world, but I’m getting some tools. I’m a female, I’m scared and I’m limited.” When the war comes, here comes the Union Army; here comes the Confederate Army. Black people were suddenly put into a different class, a different status—from slave to contraband. “What is that for real?” Contraband status was still a level of servitude, even while it provided a degree of safety and protection. In the delicate wartime situation, options were limited—formerly enslaved people could go with the Army or go back to the plantation. Ahhh … probably not much to consider.

President Lincoln had somewhat provisionally approved General Butler’s decision to designate enslaved people gathered by the Army from Confederate lands as contraband. He chose that designation because the Fugitive Slave Laws were in effect, which would bind anyone who identified fugitive slaves to return them to their captors. The general was faced with the choice when three escaped Black men sought asylum at Fort Monroe. The general, who was also a lawyer, decided to use Virginia’s claim that it was a foreign country after seceding from the U.S. to assert that they were therefore not a beneficiary of the Fugitive Slave Laws.

Group of “contrabands” at Foller’s House. Source: Library of Congress

Remember—contraband weren’t free. The Emancipation Proclamation wasn’t issued until 1865/66. Free movement in big cities was precarious. Black people had to carry some kind of paper, some identification that declared their right to walk independently among White folk, such as a letter saying that they were a free person. However, the letter was no guarantee. Plenty of people were snatched off the ground, out of cities, who had letters of freedom. It didn’t matter. They still were more valuable as slaves. So, most Blacks didn’t venture out unless they had some autonomy. Something had to back them, to give them credence, unless they were going all the way to Canada, Nova Scotia, British Columbia and such. They migrated to those places until some of provinces stopped letting Blacks come in. New York and Pennsylvania were still considered slave country, because slave catchers and bounty hunters would come there, capture them again and return them to the plantations.

In addition to the protection the Army afforded, soldiers received a little pay, they had food, clothes—the connection gave them something so they didn’t feel alone, not just out there. They were part of a group. As contraband, Williams saw a way to better herself. She taught herself how to shoot and ride and she learned all the survival and other skills that the Army was teaching. Being out there on the trail, day in and day out, marching, fighting, whatever they did—she did all that. I look at it like, she was honing her skills, gaining more experience. Yes, she could cook, she could clean, she knew how to sew. She was doing all those kinds of things already. At this stage, she has gained skills to become self-sufficient, and has a greater sense of self.

Maneuvering from contraband into actually being a soldier, now she’s in disguise mode, which entails real danger. She stepped boldly into a precarious situation. Any time you have a group of men—Black, White or whatever—and there’s a woman around, you know—. So, she had to always keep that at bay. She never bathed with the guys; it was always, “I’ve got something else to do,” or some other excuse. When she had a bout of sickness and had to visit the infirmary, it was inevitable that she would be discovered and dismissed.

After she was discharged from the Army, I imagine Williams thinking, “I’ve got all these skills, but I’m back to being a woman again.” At that time, a woman didn’t have rights or dignity. She wasn’t thought of in high esteem. Even so, Williams moves forward. She gets married, starts a business cooking, cleaning and doing seamstress work. Then she absorbed another hit. While they were in New Mexico or Arizona, her husband stole her belongings and money, and he left. She went to the authorities and recovered some of her possessions, but the money was all spent. Undefeated, she went to another small town and set up a café, becoming self-employed again. However, her health is failing. The denial of her Army pension limits her access to to health care. Ultimately, Cathay Williams succumbed to her various illnesses at just 49 years of age.

I would say she lived a great life, because she lived a life of growth and development. She started out as an enslaved person, became contraband and ended up a free, independent, self-sufficient woman. She made her own way.

We know Cathay Williams’ story because of a lone newspaper reporter who happened to come through one of the small towns where she operated her business. The reporter asked around about interesting people in town, and had also heard a little about her. Her service and independence were well known, and the townspeople had started asking, “Who are you and where do you come from?” She told them she had been in the Army. They didn’t necessarily believe her because she was a woman. However, because of the detailed accounts and direct information that she could give them, they were like, okay. The reporter interviewed her, she showed him her discharge papers and told her story, and that’s how the world came to know about the legendary Cathay Williams.

Bust of Cathay Williams. Mural and Statue Safari Stop #12 at the Richard Allen Cultural Center and Museum in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Even though her ending is sad, Cathay Williams is an amazing African Treasure. Learning about her set me out on a mission to learn more and more. I’m still looking for information, but there’s not a lot out there. Many reports about her repeat information from other sources. Daisy, to me, gave the best story. Learn more about Dr. Daisy Century in Part II of this story of two great Treasures of the African Diaspora.